Lincoln - Shields Duel

ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND JAMES SHIELDS DUEL

September 22, 1842

Under the pen name of “Aunt Rebecca,” Abraham Lincoln, then an

attorney, wrote a series of letters to the Sangamon Journal keenly

satirizing young James Shields, auditor of the State of Illinois on

the Democrat ticket. Shields’ dress, his "dudeish" manners, and his

self-proclaimed status as a "ladies’ man," drew down ridicule from

others. In his first letter to the newspaper, Lincoln wrote the

following, referring to “Jeff,” a farmer: “I’ve

been

tugging ever since harvest, getting out wheat and hauling it to the

river, to raise State Bank paper enough to pay my tax this year, and

a little school debt I owe; and now just as I’ve got it…, lo and

behold, I find a set of fellows calling themselves officers of

State, have forbidden to receive State paper at all; and so here it

is, dead on my hands.” When “Rebecca” identifies Shields as one of

the “officers of state” and reads aloud from his declaration against

accepting state money, Jeff explodes. “I say–it-is-a-lie…. It grins

out like a copper dollar. Shields is a fool as well as a liar. With

him truth is out of the question.” Lincoln went on to deride Shields

on the social scene, with “Jeff” recalling Shields at a recent fair

attended by the eligible women of Springfield: “His very features,

in the ecstatic agony of his soul, spoke audibly and distinctly –

‘Dear girls, it is distressing, but I cannot marry you all. Too well

I know how much you suffer; but do, do remember, it is not my fault

that I am so handsome and so interesting.’” The letter ended

with an appeal to the editor: “Let your readers know who and what

these officers of State are. It may help to send the present

hypocritical set to where they belong and to fill the places they

now disgrace with men who will do more for less pay.” Lincoln signed

the letter, “Rebecca.”

been

tugging ever since harvest, getting out wheat and hauling it to the

river, to raise State Bank paper enough to pay my tax this year, and

a little school debt I owe; and now just as I’ve got it…, lo and

behold, I find a set of fellows calling themselves officers of

State, have forbidden to receive State paper at all; and so here it

is, dead on my hands.” When “Rebecca” identifies Shields as one of

the “officers of state” and reads aloud from his declaration against

accepting state money, Jeff explodes. “I say–it-is-a-lie…. It grins

out like a copper dollar. Shields is a fool as well as a liar. With

him truth is out of the question.” Lincoln went on to deride Shields

on the social scene, with “Jeff” recalling Shields at a recent fair

attended by the eligible women of Springfield: “His very features,

in the ecstatic agony of his soul, spoke audibly and distinctly –

‘Dear girls, it is distressing, but I cannot marry you all. Too well

I know how much you suffer; but do, do remember, it is not my fault

that I am so handsome and so interesting.’” The letter ended

with an appeal to the editor: “Let your readers know who and what

these officers of State are. It may help to send the present

hypocritical set to where they belong and to fill the places they

now disgrace with men who will do more for less pay.” Lincoln signed

the letter, “Rebecca.”

After reading the letters in the newspaper, Shields fumed, which

only

Shields wrote, “I have become the object of slander, vituperation

and personal abuse. Only a full retraction may prevent consequences

which no one will regret more than myself.”

Lincoln replied that he could give the note no attention, because

Shields had not first asked if he really was the author of the poem.

Shields wrote again, but Lincoln replied he would receive nothing

but a withdrawal of the first note, or a challenge. The challenge

came, and was accepted. Lincoln chose broadswords as the weapon, and

the place of the duel - Sunflower Island, directly across from Alton

– was selected. The islands in the Mississippi River at that time

were in a “no man’s land,” and were out of the jurisdiction of both

Missouri and Illinois. Contrary to what you may read on different

websites, the island where the Lincoln – Shields duel was held was

not “Bloody Island,” which was directly across from St. Louis (and

now a part of Illinois), and has its own history of duels

(Benton-Lucas, August 12, 1817; Barton-Rector, June 30, 1823;

Biddle-Pettis, August 26, 1831; and Brown-Reynolds, August 26,

1856). To read more on “Bloody Island,”

please visit this website.

Shields was only five feet, nine inches tall, while Lincoln stood at

six feet, four inches. But Shields was stubborn, ambitious,

perseverant, and had served in the Black Hawk War. Later in the

Mexican War, he would take a bullet in the chest at the Battle of

Cerro Gordo. After surgery and nine weeks of recuperation, he

returned to his command. This was clearly a man who would not run

from a fight.

On the morning of September 22, 1842, Shields and Lincoln arrived in

Alton. The party took breakfast at the Franklin House, 206 State

Street, in Alton (now the Lincoln Lofts apartments), and at about

10:30 a.m., proceeded to a ferry boat which was owned and run by a

Mr. Chapman. The boat was propelled by two horses, which worked

around a windless at one end of the boat deck. A Telegraph reporter

by the name of Mr. Southers (the owner and editor of the newspaper,

John Bailhache, was out of town), a man by the name of John

Broughton, and Dr. Thomas Hope accompanied Lincoln and Shields and

their party to Sunflower Island, directly across from Alton. A spot

was cleared by the party, and Shields took a seat upon a fallen log

on one side, with Lincoln on the other. Their “seconds” proceeded to

cut a pole about twelve feet long, and placed it in two stakes with

crotches in the end, about three feet above the ground. The men were

to stand on either side of the pole, and fight across it. A line was

drawn on the ground on both sides, three feet from the pole, with

the understanding that if either stepped back across the line, it

was to be considered a concession and an end to the duel.

Finally, Dr. Hope sprang to his feet and faced Shields. He blurted

out, “Jimmie, you G—D--- little whippersnapper, if you don’t settle

this, I will take you across my knee and spank you!” This was too

much for Shields, and he yielded. A note was prepared by Shields and

sent across the line to Lincoln, which inquired if he was the author

of the poem in question. Lincoln replied that he was not, and mutual

explanations and apologies followed.

The men returned to the boat, chatting in a friendly manner. John

Broughton took a log and put it at one end of the boat, and covered

it with a red shirt to make it look like the figure of a man covered

with blood. As the boat reached Alton, the landing was crowded with

people who were waiting to learn the result of the duel. When they

saw the dummy at the end of the boat, some almost stepped into the

water to see who it was that had been slain.

News of the “duel” spread among the Alton community. The editor of

the Alton Telegraph, John Bailhache, who had recently returned from

a trip, wrote a scathing article regarding the action of the two

men. Both Lincoln and Shields were personal friends of his, and he

called their action disgraceful and unfortunate. Bailhache further

stated that a friendless, penniless, and obscure person would be

placed in jail and then sentenced to the penitentiary for the same

action. He called upon Attorney General Lamboro to exercise zeal in

bringing the two men to justice. However, Bailhache was happy the

two men were returned to their family and friends unscathed, and

hoped the citizens of Springfield would select some other town

rather than Alton, if they intended to take each other’s life in the

future.

Later, Lincoln and Shields rarely spoke of the duel. Once when asked

about it, Lincoln brushed the subject aside and spoke no further on

the matter.

In later years, Sunflower Island - where the duel was held - took on

the name of Smallpox Island, after the Confederate soldiers were

housed in a hospital there during the smallpox epidemic. Later, it

was known as McPike Island, Ellis Island, and Bayless Island. The

Lincoln – Shields Recreation Area in Missouri was named after the

event. There a monument stands in memory of the soldiers who were

housed in the hospital on the island during the Civil War. Most of

the island was destroyed by flooding during the construction of the

bridges and dam.

DISTINGUISHED GENTLEMEN ATTEMPT TO ASSASSINATE EACH OTHER

Source: Alton Telegraph, October 01, 1842

Our city was the site of an unusual scene of excitement during the

last week, arising from a visit of two distinguished gentlemen of

the city of Springfield, who, it was understood, had come here with

a view of crossing the river to answer the "requisitions of the code

of honor," by brutally attempting to assassinate each other in cold

blood.

We recur to this matter with pain and the deepest regret. Both are,

and have been, for a long time, our personal friends. Both we have

everJohn Bailhache, Editor of the Alton Telegraph esteemed in all

the private relations of life, and consequently regret that what we

consider an imperative sense of duty we owe to the public, compels

us to recur to the disgraceful and unfortunate occurrence at all.

We, however, consider that these gentlemen have both violated the

laws of the country, and insist that neither their influence, their

respectability, nor their private worth should save them from being

made a menable [sic] to those laws they have violated. Both of them

are lawyers - both have been Legislators of this State, and aided in

the construction of laws for the protection of society - both

exercise on small influence in community - all of which, in our

estimation, aggravates instead of mitigating their offense. Why,

therefore, they should be permitted to escape punishment, while a

friendless, penniless, and obscure person, for a much less offense,

is hurried to the cells of our county jail, forced through a trial,

with scarcely the forms of law, and finally immured within the

dreary walls of a Penitentiary, we are at a loss to conjecture. It

is a partial and disreputable administration of justice, which,

though in accordance with the spirit of the age, we must solemnly

protest against. Wealth, influence, and rank can trample upon the

laws with impunity; while poverty is scarcely permitted to utter a

word in its defense if charged with crime in our miscalled temples

of justice.

Among the catalogue of crime that disgraces the land, we look upon

none to be more aggravated and less excusable than that of dueling.

It is the calmest, most deliberate, and malicious species of murder

- a relict of the most cruel barbarism that ever disgraced the

darkest period of the world - and one which every principle of

religion, virtue and good order, loudly demands should be put a stop

to. This can be done only by a firm and unwavering enforcement of

the law, in regard to dueling, towards all those who so far forget

the obligations they are under to society and the laws which protect

them, as to violate its provisions. And until this is done, until

the civil authorities have the moral courage to discharge their duty

and enforce the law in this respect, we may frequently expect to

witness the same disgraceful scenes that were meted in our city last

week.

Upon a former occasion, when under somewhat similar circumstances

our city was visited, we called upon the Attorney General to enforce

the law and bring the offenders to justice. Bills of indictment were

preferred against the guilty; but there the matter was permitted to

rest unnoticed and unexamined. The offenders in this instance, as in

the former, committed the violation of the law in Springfield; and

we again call upon Mr. Attorney General Lamboro, to exercise a

little of that zeal which he is continually putting in requisition

against less favored but no less guilty offenders, and bring all who

have been concerned in the late attempt at assassination to justice.

Unless he does it, he will prove himself unworthy the high trust

that has been reposed in him.

How the affair finally terminated, not having taken the trouble to

inquire, we are unable to say. The friends of Mr. Shields and Mr.

Lincoln claim it to have been settled upon terms alike, honorable to

both, notwithstanding the hundred rumors - many of which border upon

the ridiculous - that are in circulation. We are rejoiced that both

were permitted to return to the bosom of their friends, and trust

that they will now consider, if they did not do it before, that

rushing unprepared upon the untried scenes of Eternity is a step too

fearful in its consequences to be undertaken without preparation.

We are astonished to hear that large numbers of our citizens crossed

the river to witness a scene of cold-blooded assassination between

two of their fellow beings. It was no less disgraceful than the

conduct of those who were to have been the actors in the drama.

Hereafter, we hope the citizens of Springfield will select some

other point to make public their intention of crossing the

Mississippi to take each other's life than Alton. Such visits cannot

but be attended not only with regret, but with unwelcome feelings;

and the fewer we have, the better. We should have alluded to this

matter last week, but for our absence at Court. ~Signed John

Bailhache, Editor, Alton Telegraph

STORY BY AN EYE WITNESS - THE CHALLENGE - THE BATTLE

Source: Alton Evening Telegraph, February 25, 1902

There has been so many versions of the incidents of the duel, mostly

for the purpose simply to produce a sensational article, it becomes

a duty to history to give a simple and correct statement by an

eye-witness of what actually took place. There are several citizens

here in Alton now who were on the river bank or on the horse ferry

which carried the excited company over the Mississippi river from

the foot of State street to the island in sight and opposite to the

city of Alton - which is now much larger than then - Mr. Edward

Levis of Alton; also a Mr. George Booth of Chicago; and James E.

Starr of Portland, Oregon, still living; and the late Captain Joseph

Brown, ex-mayor of Alton and ex-mayor of St. Louis; and Mr. W. H.

Souther, now deceased, who was also on the old houseboat among the

crowd, have given us the Alton end correctly. The writer of this,

though four years too late to witness this exciting and most

humorous termination of what promised to be a bloody affair, became

acquainted personally with all the individuals connected with it,

and obtained the facts as herein detailed, also from the late Judge

John Bailhache, the editor of the Alton Daily Telegraph. The

Springfield end is given as I received it there. The Miss Mary Todd,

named, became later Mrs. Abraham Lincoln, and Miss Julia Jayne, the

wife of Judge Lyman Trumbull - both of whom have sons now residing

in Chicago. The Inter-Ocean of Chicago, a few days since, gave an

illustrated article of the duel in which not a single reference was

correctly stated. ~Henry Guest McPike.

Here is an exact copy of the statement of Mr. Southers, who was a

reporter on the Telegraph at the time:

James Shields was Auditor of State, elected on the Democratic

ticket, and from his swagger in dress, his dudish manners, and his

evident self-satisfaction with himself as a ladies man, quickly drew

down on himself the ridicule of the Whips. Lincoln wrote a series of

letters to the Sangamon Journal, after the fashion of the "Bigelow

Papers," keenly satirizing young Shields. He fumed under these

assaults, which only encouraged their continuance. Finally a poem

was sent to the Journal by Mary Todd and Julia Jayne, in which

Shields was pictured as receiving a proposal of marriage from "Aunt

Rebecca," and later another rhyme followed, celebrating the wedding.

In the words of the bounding west, these mischievous girls made life

exceedingly wearisome for the dudish young State auditor. At the

appearance of the last poem, Shields went to the editor of the

Journal in a towering rage and demanded the name of his tormentor.

The editor, in a quandary, went to Lincoln, who unwilling that Miss

Todd and Miss Jayne should figure in the affair, ordered that his

own name be given as the author.

Mr. Lincoln Challenged

Shortly after, Lincoln received a letter from Shields demanding an

apology. To this Lincoln replied that he could give the note no

attention because Shields had not first inquired whether he really

was the author of the poem. Shields wrote again, but Lincoln replied

that he would receive nothing but a withdrawal of the first note or

a challenge. The challenge came, was accepted, and Lincoln named

broadswords as the weapons to be used, the place selected being the

Mississippi riverbank opposite Alton.

Mary Todd Lincoln

It was on the morning of September 22, 1842 that Shields and Lincoln

arrived in Alton. I was then a printer and reported on the Alton

Telegraph, and had received an intimation of the coming duel, which

made me resolve to see it, if possible. The dueling party took

breakfast at the Franklin house, and about half past 10 in the

forenoon, proceeded to the ferry boat, which was owned and run by a

man by the name of Chapman. The boat was propelled by two horses,

which worked around a windless at one end of the boat deck, and I

made arrangements with Chapman to drive these horses. A young fellow

by the name of Broughton also smuggled himself aboard as a horse

driver, making just ten of us in all, as I remember.

Lincoln and his party sat at one side of the boat, and Shields and

his party at the other. The only thing which looked belligerent

about the equipment were six long cavalry sabers which lay on the

deck, in charge of Lincoln's seconds. There was no talking between

the opposite sides, and everything proceeded as solemnly and

decorously as at a funeral.

On the Battleground

Abraham Lincoln

Arriving on the opposite shore, which was a wilderness of timber, a

spot partially cleared was selected as the battleground. Shields

took a seat upon a fallen log on one side of the little clearing,

and Lincoln ensconced himself on another at the opposite side. The

seconds then proceeded to cut a pole about twelve feet long, and two

stakes with crotches in the end. The stakes were driven in the

ground and the pole laid across the crotches, so that it rested

about three feet above the ground. The men were to stand one on

either side of the pole and fight across it. A line was drawn on the

ground on both sides, three feet from the pole, with the

understanding that if either combatant stepped back across his own

line it was to be considered a giving up of the fight. This, you

see, would keep the fighters within range of each other all the

time, as neither could get more than three feet away from the pole,

and the swords seemed to me to be at least five feet long. After all

these arrangements had been completed, the seconds rejoined their

principals at the different sides

Shields Backs down

Lincoln remained firm, and said that Shields must withdraw his first

note and ask him whether or not he was author of the poem in

theLincoln - Shields Duel Journal. When that was done, he said, he

was ready to treat with the other side. Shields was inflexible and

finally Dr. Hope got made at him. He said Shields was bringing the

Democratic party of Illinois into ridicule and contempt by his

folly. Finally, he sprang to his feet, faced the stubborn little

Irishman and blurted out: "Jimmie, you G--- D--- little

whippersnapper, if you don't settle this, I will take you across my

knee and spank you." This was too much for Shields, and he yielded.

I believe Dr. Hope would have carried his threat into execution if

he hadn't. A note was solemnly prepared and sent across to Lincoln,

which inquired if he was the author of the poem in question. Lincoln

wrote a formal reply in which he said that he was not, and then

mutual explanations and apologies followed.

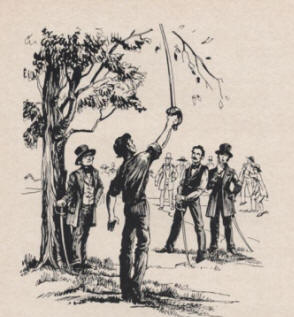

I watched Lincoln while he sat on his log, waiting the signal to

fight. His face was grave and serious. I could discern nothing of

'Old Abe,' as we knew him. I never knew him to go so long before

without making some sort of a joke, and I began to believe he was

getting frightened. But presently he reached over and picked up one

of the swords, which he drew from its scabbard. Then he felt along

the edge of the weapon with his thumb like a barber feels of the

edge of his razor, stretched himself to his full height, stretched

out his long arm and clipped off a twig from a tree above his head

with the sword. There wasn't another man of us who could have

reached anywhere near the twig, and the absurdity of that

long-reaching fellow fighting with cavalry sabers with little

Shields, who could walk under his arm, came pretty near making me

howl with laughter. After Lincoln had cut off the twig, he returned

the sword to its scabbard with a sigh, and sat down, but I detected

the gleam in his eye, which was always the forerunner of one of his

inimitable yarns, and I fully expected him to tell a side splitter

right there in the shadow of the grave.

After things had been adjusted at the dueling ground, we returned to

the ferry boat, everybody chatting in the most friendly manner

possible. But it must have been an awful trial to Lincoln to hold in

and not 'josh the life out of Shields.' Before we started back, John

Broughton got a log and put it at one end of the ferry boat and

covered it with a red shirt in such a manner that it looked like the

recumbent figure of a man covered with blood. When we reached Alton,

the landing was crowded with people who were there to learn the

result of the duel. When they saw the dummy at the end of the boat,

they almost crowded into the water to see who it was that had been

slain. I enjoyed this scene, although it was clearly offensive to

Shields."

LINCOLN – SHIELDS DUEL

Source: Alton Telegraph, October 4, 1877

A story, full of inaccuracies, concerning the great duel (?) between

Abraham Lincoln and General James Shields has lately been going the

rounds of the newspapers. We have recently learned some facts in

reference to this affair from the Hon. George T. Brown, who was

present and witnessed the closing scenes in the somewhat remarkable

drama spoken of. The misunderstanding originated, as has been

correctly stated, through a publication in the Sangamo Journal,

written by Miss Julia Jayne, afterwards Mrs. Lyman Trumbull, but for

which Mr. Lincoln assumed the responsibility. This led to a

challenge from Shields, who felt himself aggrieved by the article in

question. Lincoln, being the challenged party, chose broadswords as

the weapons, hoping thereby to terminate the combat without

bloodshed, and the parties and their friends came to Alton, crossed

the river, and selected a spot a few hundred yards above a point

opposite Piasa Street as the battleground. Mr. Merrimon of

Springfield was the second of Mr. Lincoln. Our informant, who was a

mere lad at the time, cannot recall the name of the person who

performed the same office for General Shields. Through the friendly

efforts of Colonel E. D. Baker, Colonel John J. Hardin, and others,

the matter was amicably arranged on the battleground, and the

principals were ever after firm friends. Hardin afterwards became

Colonel of an Illinois Regiment, and was slain on at the Battle of

Buena Vista in Mexico. Baker was the Colonel of a California

Regiment, and was killed during the bloody battle of Ball’s Bluff,

at the commencement of the War of the Rebellion.

But to return to the duel. The parties crossed the river on a

two-horse ferry boat, with but few persons in Alton knowing anything

of the affair. Our informant, however, got wind of it, and crossed

in a skiff, and witnessed the proceedings on the ground. As they all

returned, a fix-foot constable of Alton named Jake Smith said that

it was too bad that there had been no fight, and to keep up

appearances, got a log of wood, laid it down on the deck of the

boat, took his camlet cloak, and wrapped it around the log with the

red lining on the outside, in such a manner that it looked like a

prostrate, bloody human form. He also procured a branch from a tree,

and waved it over the object as though keeping away insects, and in

this way badly sold the crowd that he collected on the levee in

anticipation of seeing a corpse or two.

Our informant also states that this “duel” was once spoken of to Mr.

Lincoln at Washington, while he was President, when he earnestly

requested that it might never again be mentioned, as he was

profoundly ashamed of the whole business. General Shields could

never be induced to speak of it. The accounts that locate the

“battleground” on Bloody Island near St. Louis miss the spot by

about twenty-five miles. [Note: the “battleground” was on Sunflower

Island, directly across from Alton.]

LINCOLN – SHIELDS "DIFFICULTY"

Source: Alton Daily Telegraph, February 4, 1887

Most of the accounts of the duel (that did not come off) between

Lincoln and Shields state that the parties went to Bloody Island in

the Mississippi River, for the proposed encounter. The two noted

men, with their friends, came from Springfield to Alton in

carriages, and then went to what is now known as Bayless Island,

opposite Alton. Blood Island is about 25 miles below, constituting

part of East St. Louis.

The trip across the river was made on a ferry boat, and the affair

having “got noised around,” the people of Alton were greatly

excited. When the parties were returning to Alton, some wag in the

party took a log of wood, spread over it a red garment, and exposed

it near the bow of the boat, thus representing a bloody, prostrate

form, as though one of the duelists had fallen a victim to

broadsword practice, this weapon being similar to the Scotch

claymore, being the one agreed upon. Mr. D. S. Hoaglan, still a

resident of Alton, was here at that time, and was an intimate friend

of Mr. Lincoln’s. He states that Dr. R. W. English, our last

Democrat postmaster, then a resident of Carrollton, was the person

who arranged the difficulty between Lincoln and Shields, without

bloodshed.