Piasata, The Indian Maiden

Return to Native American main page

THE STORY OF PIASATA, THE INDIAN MAIDEN

And the Legend of the Piasa Bird

As told by James R. Wilson, resident of Jersey County, Illinois,

1818 – abt. 1836

The following newspaper article was found in the Daily Democrat,

Jerseyville, Jersey County, Illinois, and contains lengthy letters

from Mr. James R. Wilson, of McComb City, Mississippi. These letters

from Mr. Wilson detail his story as a youth in 1828, living near

where Delhi now stands, Jersey County, Illinois, where he, along

with two other lads (Joe and Sam), met a Native American family at

the mouth of the Piasa Creek (where it empties into the Mississippi

River near Lockhaven). The three youths fell in love with the

Chief's daughter, Piasata.

Source: The Daily Democrat, 1900

Introductory Letter from Mr. James R. Wilson:

Dear Sir,

The story of "Piasata," which I have written and mailed to you for

publication and in which is given a partial history of three Jersey

county boys during the early settlement of your State, is more full

and complete, and therefore longer than I intended making it. I was

led to commence this sketch by reading in some paper an item in

regard to the legend of the "Piasa Bird;" and as I am perhaps the

only man living who knows anything of the true history of this bird,

at what period of time it lived, and how it was destroyed, I felt it

a duty I owed to posterity to give to the public all the information

I possess, and state how I came into possession of it. In attempting

to do this, youthful memories have crowded so upon me, that I have

described many incidents not connected with the bird, but which I

believe will interest your readers, especially the younger portion

of them.

I go to New Orleans shortly and do not know when I shall return, but

if my story interests you and you should desire further information

on any subject with which I am acquainted and able to give, if you

address me, care of Dr. J. H. Plunkett, McComb City, Mississippi, I

will get your letter.

Yours truly, James R. Wilson

PIASATA AND THE LEGEND OF THE GREAT PIASA BIRD

Chapter I

I am an old man now; more than four score [80] years have passed

over my head, yet, thanks to my early training and a vigorous

constitution, I am still quite active and appear to be many years

younger. The incidents I am going to relate took place nearly three

quarters of a century ago, yet they were so indelibly stamped on my

mind, that they are as plain and vivid today, as though occurring

only a few months ago. At that time (1828), I lived in Illinois, in

what was afterwards Jersey county (it may have been so then, I do

not remember), about two miles from where the village of Delhi now

stands, but there was not a house there then, nothing but hazel

patches, scrub bushes and prairie. My parents located there in 1818,

the year that Illinois was made a State, and when I was three years

old. Near our place, two other families had taken up homes, and each

had a boy about my own age (thirteen); one was Joe, the other, Sam,

and I was Jim. Our outdoor labors in building, fencing and clearing

up new ground made us strong, active, healthy lads, and we being the

only boys in the neighborhood, soon formed an attachment for each

other that grew into a friendship which was only broken by the death

of the other two - many years afterward.

Our parents were quite indulgent to us in one respect at least; if

we worked well during the week they allowed us every Saturday

afternoon as a half holiday to enjoy or spend as we pleased. These

holidays, during spring, summer and autumn, if the weather would

permit, we invariably spent along the banks of a stream called Piasa

Creek, which was a mile or more distant from our homes. This creek

was much larger then than it is now, in fact there were then many

little creeks and lakes in that portion of the state that have since

entirely disappeared. The clearing up of the hazel patches and scrub

timber, and the cultivation of the soil destroyed the drainage and

the loosened earth washed in and filled them up. All these creeks

were then literally alive with fish, and should I tell the number of

sun perch, bream (or goggle eyes) and other varieties that we boys

often caught in a few hours with our rude hooks and lines, this

generation would not believe it. We knew every crook and bend of

this Piasa Creek for miles up towards its source and down towards

its mouth, and had fished and bathed along the entire distance.

This much of an introduction has been necessary to make the story I

am telling intelligible. There were no Indians in that portion of

the State then, and neither of us boys had ever seen one. All we

knew of them was from what we had gleaned out of the few books owned

by our different families, and from stories we had heard told by our

parents. I know that our belief was, that an Indian was always on

the war path, with rifle or bow and tomahawk, seeking to kill a

white man or women and children.

One Saturday in the first week of June, we boys having a full

holiday, got to the creek early in the forenoon and decided that we

would go down the stream farther than we had ever been before.

Therefore, without stopping any place to fish, we walked briskly

along, following the old "buffalo trail" until we concluded that we

were at least two miles beyond our regular stopping place, when, on

suddenly turning a bend of the creek, we saw before us an Indian

wigwam, and were confronted by an Indian dog, which made no attempt

to bite us, but certainly made noise enough for half a dozen dogs of

its size. To say that we were frightened but poorly expresses the

situation. We expected every second to hear the crack of rifles and

feel bullets tearing through our bodies; but just as I had said

"Indians, boys, let's run for our lives," and we had turned about to

do so, we beheld a tall, dignified looking Indian quietly standing

in the path before us. Talk about teeth chattering, knees trembling,

eyes bulging, and all the other symptoms of fright - I am satisfied

we had all those and the balance of them, if there are any more. I

know that I expected to see him draw his tomahawk and scalping

knife, as I thought every Indian must have them, and I am certain

that the hairs on our heads stood up as straight as ever a porcupine

raised its quills. But just then, when we believed all was over with

us and our lives were not worth the fishing poles we carried, the

Indian raised his hand and motioning us backward, said in broken

English, "kaw, kaw," (no, no) "white boy no run, heap good Indian,

no hurt white boy." I have wandered over many states since then and

have been charmed with sweet strains of music and song, but I think

that the rough guttural tones of that Indian's voice were sweeter

far to me then than any note I have ever heard since. Seeing that

our fears were subsiding, the Indian again motioned us backward,

saying, "no run, me no hurt. See wigwam. See squaw. See Piasata."

It does not take young people long to get acquainted and in an

hour's time we were all talking to her and listening to her replies

in broken English. She was certainly very pretty, but she did not

have those extremely small feet and hands that many writers give to

their Indian heroines or sweethearts, and she was certainly ours

from that day onward; and for months afterward there was a great

rivalry between us boys as to which of us should command the

greatest share of her attention.

Chapter II

She showed us many things of her making (moccasins, leggings and

other fancy articles), together with her father's war bow and quiver

of arrows, and a flint lock rifle, which she said was to "heap kill

buffalo and Indians." She also showed us a smaller bow and arrows,

which she said was to "heap shoot mark." During all our conversation

with her, the old Indian, though seeming very much interested, did

not speak to us, only muttering an occasional "ugh" or "kaw" (yes or

no), but when she showed us the smaller bow and arrows, he said,

"white boy shoot bow?" We nodded assent and he then took them and

saying, "Piasata heap shoot mark," started off up the road we had

come, motioning us to follow him. We did so, understanding that he

was challenging us to shoot against her. Now, we boys all had bows,

though crude in comparison to this one, but we thought we could do

some pretty fair shooting and were perfectly willing to have a trial

with her. Stopping where there was a straight stretch of road for a

hundred yards or more, he took his knife and cut off the outer bark

of a tree, making a mark about six inches in diameter; then,

motioning us to follow him, he walked off fully seventy-five yards

from the tree, then turned and commenced to string up the bow.

Piasata stood by, seeming perfectly satisfied, but we boys made him

understand that we could not shoot so far and wanted to go much

nearer to the mark. He gave us a look of disgust and muttered, "ugh,

white boy shan-go-da-ya," (which we afterwards learned meant

coward). He walked back to the place we indicated, about forty yards

from the mark; then handing me the bow and arrow; he said "shoot

heap straight." Well, I took a good long aim, shot, and missed the

tree (about a foot in diameter); Sam then shot and did the same; Joe

followed suit, hitting the tree, but his arrow was sticking about

two feet under the mark. It was now Piasata's turn to shoot and I

hoped that she would miss the tree also. There were six arrows left

in the quiver. She selected three and handing her father two to hold

for her, she stepped on the spot we had shot from and almost

instantly let fly an arrow, followed by another as quick as her

father could hand it to her and both struck the mark, one in the

edge, the other near the center. But without giving us time to

praise or congratulate her, she took the last arrow and walked up

the road until fully one hundred yards from the tree, then turned

and shot nearly as quickly as before, the arrow striking within

three inches of the mark. The Indian offered us boys another arrow,

but we were discouraged and disgusted and would not shoot again. We

complimented Piasata on her skill and told her we were glad she beat

us, which was just one of our little lies. She tried to console us

by saying, "never mind, white boy shoot heap good someday." But I

made up my mind to break my bow and arrow as soon as I got home, and

never shoot again. The old Indian made no comments, but his face

showed that he was very much pleased at our defeat and with her

shooting, though, of course, he knew how it would end before the

trial.

As we wanted to take home some fish to show for our day's outing, we

now prepared our lines and, in an hour, had caught all that we

wished to carry; then telling our newly made friends good bye, and

with this rather doubtful invitation from the old Indian to renew

our visit, "ugh, white boys heap come more some time," we started

homeward.

On the way, we decided on two things; first, not to say anything to

our parents for the present about our Indian friends, and second,

that we were all three desperately in love with Piasata.

The next day, Sunday, was ours, and we agreed to meet as early as

possible at the old ford (the road leading from Delhi to Alton

crosses the creek at the place) and each to bring something for

ourselves and Indian friends to eat. We met about nine o'clock and

upon making an inventory of the victuals we had secured, we found

the result to be as follows: Sam had his pockets full of biscuits

and the leg and wing of a chicken; Joe had half of a "Johnny cake"

and a chunk of boiled venison. He had split open the cake of corn

bread and had put in a big lot of butter, then had wrapped it up in

about a yard of calico. The heat of the sun and the warmth of is

body had caused the butter to melt and run out and one side of his

tow-linen coat looked as if he had fallen into a kettle of soap

grease to which the calico had added sundry red and green spots. As

to myself, I had hooked a dewberry pie, a small piece of ham and a

chunk of "corn pone." I had tied them up in my father's many-colored

handkerchief, and which for convenience in carrying I had swung over

my shoulder. The juice had run out of the pie and trickled over my

tow-linen coat until, with stains added from the handkerchief, it

had about as many colors as the famous coat worn by Joseph. We were

in a pickle, and how on our return home to account for the condition

of our clothes without giving up our secret or telling a plain lie,

bothered us. But it is hard to dampen the spirit of a frolicsome boy

and we were soon laughing over our mishaps while trudging briskly

along the trail that led to the Indian's camp. On our arrival, the

old Indian and his wife merely nodded and said "ugh," while Piasata

shook hands with us, but it was plain to be seen from their faces

that we were welcome.

We presented our motley lot of provisions to the squaw, who was

certainly much pleased to receive them. She was a good looking

half-breed, about thirty-five years old and a little inclined to

corpulency [stoutness], but I felt certain that the use of a little

soap and water would improve matters with herself as well as her

husband. They both dressed very much the same as I have described

Piasata, but with this difference, she was always neat and clean,

while they looked the opposite.

Chapter III

We spent the time very pleasantly for

an hour or so talking with them as best we could and each trying to

gain the largest share of Piasata's attention. I thought Joe had

gotten ahead of us by giving her his piece of greasy calico and I at

once donated my father's large cotton handkerchief, which certainly

put me in the lead, and I felt quite elated over my victory. But

now, the old Indian, who had thus far made no remarks except his

usual "ugh, ugh" or "kaw, kaw," said to us, "white boy heap run

fast." We knew this was a challenge for a foot race with Piasata and

at once nodded assent. We were really glad he made it, because

wrestling and foot racing were our principle amusements and we

considered ourselves experts at both, Sam and myself especially so.

She had beaten us with bow and arrows and we felt sure that we could

even up matters in the foot race. We made ready by removing our

shoes (we had no socks) and tying our "galluses" [suspenders] tight

around our waists, while Piasata said she was "heap ready" just as

she was. We went up the road to where we had held our shooting

tournament, the old Indian stopping at least two hundred yards from

the tree we had shot at, indicating by a sign that it was to be the

end of the race. We were again compelled to make a kick, the

distance was too great. We knew that one hundred yards was our limit

for best speed and insisted on running this distance. He reluctantly

gave in to us, muttering "ugh esa kaw mahugo tayse," (shame upon

you, no brave heart). As we did not then know the meaning of his

expression, we were satisfied with gaining our point and I felt sure

that Sam or myself would show Miss Piasata our heels.

The old Indian took his stand about one hundred yards from the tree

and signed for Piasata and myself to clasp hands ten paces back of

him, then start and "break hands" when we reached him, and "scoot."

We did so, and I being quicker than she, gained several yards on her

in the first twenty-five and began to feel a little sorry about

beating her so badly and was thinking of slowing up a little, when

phew! she moved up even with and passed me in spite of my utmost

exertions to keep up with her and reached the tree fully six yards

ahead of me. I was both worried and astonished, because I had

thought myself a pretty swift runner, but I shook hands with her

over my defeat and we went back to the starting place, she telling

me "heap short race, run faster long race." Without resting a

minute, she took Sam’s hand and they were off on their trial, she

beating him worse than myself, which so discouraged Joe that he

refused to run at all. The old Indian showed by his countenance that

he was highly pleased at our being so badly beaten and said "kaw,

white boy no heap run," and we were willing to admit that he told

the truth about it. He then, to show us the speed and wind of

Piasata, placed Joe about seventy-five yards from the tree, myself

about one hundred yards from Joe, and Sam equally as far beyond me,

thus arranging for her to beat all three of us at once, she having

to run three times as far as either of us. Well, she and Sam started

and before I could get a good ready and my lungs well inflated she

was right upon me, Sam eight or ten yards behind her, and to be

certain that I got a good start, I lit out ten or fifteen feet ahead

of her, but it was no "go." She passed me within fifty yards,

running like a deer, but she looked at me as she passed and said

"shango da ya," (coward). I called to Joe to start right then, that

it made no difference, she would beat him out anyhow. He did so and

ran his best, but she passed him before he reached the tree,

apparently running faster than at the commencement of the race. The

old Indian was mad at our unfair way of starting. I knew I had done

wrong, but I managed to make him believe that I knew Piasata would

beat us and I wanted to see how fast she really could run, which

pleased and pacified him. We laughed over our defeat, complimented

Piasata on her fleetness and told her we were glad that she had

beaten us, which was another of our little lies, as we felt bad over

it and would have beaten her if we could. She told us her real name

was We-ish-a-wa-she (running fawn). I know we all thought the name

very appropriate, only we felt sure that she could outrun a fawn.

Why she was named Piasata and could shoot so well and run so fast

will be explained hereafter.

Chapter IV

After our race, we returned to the wigwam, where we found the squaw

broiling fish over some coals, and though they did not appear to be

overly clean, we boys, upon invitation, pitched in and helped eat

them, besides a good portion of the victuals which we had brought,

gaining from the old Indian a muttered expression "that we could

heap eat better than we could run," which was true. All healthy boys

can do the same. Dinner over, which we ate from bark plates, the old

Indian filled his pipe with some villainous stuff (certainly not the

famous kinikinnick) [smoking material typically made of mixture of

various leaves or barks with other plant materials], lighted it, and

after taking a few puffs, handed it to us to do the same. We boys

did not use tobacco, but felt that we must smoke the "peace pipe"

with him and after many coughs and spits, much to his delight, we

succeeded in taking several whiffs apiece and our friendship was

cemented from that day.

After finishing his pipe, he asked us boys if we could "heap swim."

We knew what was coming and not caring to be humbled again we told

him "heap little." Fronting the wigwam, not ten yards distant, was a

"deep hole" as we called it and a pretty place to swim. but how

could we go in swimming? We could not strip off before them and we

had no extra clothes or bathing suits. The squaw, from our looks of

dismay, comprehended our difficulty and told us to take off our

shirts and moccasins (brogans), keep on our pants and we would be

"heap fixed" and that Piasata swim too. We were telling her that we

could not undress before women, when the old Indian pointed to our

shoes and shirts and said "take off," this settled it; we were

afraid to disobey him and we at once went behind the wigwam and got

out of them in a hurry. When we returned, covered with blushes

instead of shirts, we were confounded at sight of Piasata. She stood

before us draped like ourselves. She had removed moccasins, leggings

and body cloth. She wore a pair of pants only, made and fastened

around her waist and as I have before described, and this is how I

learned the manner of their making and fastening. Mothers have the

instinct of motherhood the world over, and noticing our surprise at

her appearance, she told us Indian people bathed that way and all

together. This I afterwards found to be true, I have seen scores of

both sexes, little and big, bathing together, the men wearing

breech-clouts only and the women a single skirt or short pants.

Piasata smiled at us and pointing to Sam, who was very dark skinned,

said he would make "heap good Indian," and to Joe, who was very

fair, she said he was "heap white girl boy." About myself she made

no comments and I was very much mortified over it, but was eased a

little when the old Indian said that I would make "heap strong man

someday." Though we bathed together this time, and often afterwards,

I never saw her give a sign or look that would indicate that she

felt she was acting unwomanly. She was modest in her immodesty. We

had the greatest respect for her and soon thought nothing of her

undressing to go in bathing with us (which we always did in front of

the wigwam). The old Indian and his squaw took a seat on the bank,

which was several feet above the water, and motioned for us to go

in. Piasata took the lead, diving down head foremost, we following

after her. We bathed for an hour at least, swimming and diving, each

trying to show off to the best advantage, but our principle fun and

annoyance and that which gave the greatest delight to her mother and

father, was Piasata's ducking us. We were her equals in swimming,

but she could beat us badly in diving. I believe she could see under

water, equal to a fish. She would dive down and the first thing we

knew, she would have one of us by the ankles and down we would go

also. She half drowned us, and yet she was so expert in diving away

from us, that we never succeeded in ducking her a single time.

Whenever we saw her go under water we at once made a break for the

bank, but seldom reached it in safety. Sam was her special favorite

in this sport, and I think she made him swallow enough water during

that summer to start a mill pond.

After leaving the water, we dressed ourselves, Piasata doing the

same, emerging from the tent in a fresh suit, looking more

interesting than ever. As it was time for us to start homeward, we

told them goodbye, and with an invitation to "heap come more," we

left with the incidents of a day's sport engraved upon our minds

that time never effaced. Now, the problem confronted us as to how to

account for the condition of our clothes, Joe’s and Sam’s coats were

stained and greasy, while mine looked still worse from berry and

handkerchief stains; and our pants were streaked all over with mud.

We talked the matter over as we hurried along and finally a bright

idea struck one of us, that we would fall into the creek

(accidentally of course) and get wet and stained all over alike. We

soon came to a clay bank suitable for our purpose where a small

drift log had lodged, and after removing our shoes we carefully

walked out on it and of course fell off. After several attempts to

climb back up the bank, slipping and rolling over each time, we

finally got out again, but what a sight we were, all grease and

berry stains were certainly hidden with mud. Our parents had often

seen us come from the creek wet and somewhat drabbled, but never in

our present condition; so we decided not to say anything about our

Indian friends, but to tell them how we walked out on a small log,

of its turning and our shoes slipping and we falling into the water

and climbing out up a clay bank. We felt sure from our appearance

that this little lie would be swallowed whole without hesitation or

comment. It being but little out of their way, Sam and Joe went home

with me and as it happened, their parents had spent the day with

mine and all were present when we entered the house and made our

agreed statement as to the cause of our appearance. Sam’s father

asked him some question about the locality of the log, but before he

could answer my father pointed to our shoes and asked how we managed

to fall into the water by our shoes slipping and get our clothes so

wet and muddy, yet keep our shoes dry. This settled it, we were

caught "red handed," and we then truthfully told them the whole

story about the victuals, our Indian friends and of our swimming

with Piasata. After scolding us for telling a story and reminding us

that boys were never as smart as they thought themselves to be, they

laughed at our miserable appearance until we felt disgusted over our

experiment and decided that it was best to tell the truth at all

times.

Our fathers then told us that it was not uncommon for one of two

Indian families to come up the Piasa a few miles from the

Mississippi in the early fall to fish and hunt. They would salt down

the fish, jerk (sun dry) the deer meat, then decamp before the

coming of winter. They supposed this one had come from somewhere

over in Missouri, but could not account for his appearance before

the commencement of the hunting season. They commented a little on

our choice of company, but said they had no objection to our

visiting them. This settled it, each of us was now sure that someday

Piasata would be his wife and that we could never, no never, be

happy if we failed to get her.

Chapter V

The incidents related in the foregoing chapters fitly describe our

amusements during the entire summer and early fall. We seldom failed

to visit our Indian friends on Saturday afternoons and Sundays and

always met with a nod of welcome from the old Indian with his "ugh,

ugh," and with a warm reception from Piasata, who soon learned from

us to speak very good English, while she in turn taught us her

language so that we could, and often did, carry on our conversations

in her own tongue, which I afterwards found out was the Algonquin.

The old Indian was of the Piasa tribe, a branch of the Algonquins,

and had been a noted chief among them after leaving the Piasa and

was a hereditary chief in his own tribe. He was born near where his

wigwam then stood, as were his father and grandfather before him.

After we boys learned to talk with him in his own language, he

became much more communicative. He told us of his tribe, their

history as he knew it, and the history of the great Piasa bird and

how they destroyed it. The events I am speaking of were in 1828, or

72 years ago. The Indian was then, as he counted by "moons," 67

years old and must have been born about 1760. His father, he said,

was 25 years older than himself and must therefore have been born

about 1735. He told us of things that took place along the Piasa

(told him by his father) as far back as 1745, and of events that

happened in that portion of the state (told him by his grandfather)

as far back as 1720, and by his great grandfather as far back as

1690. I could tell many of them, but it would make this story too

long. They were not traditions, as his father, grandfather and

great-grandfather had taken part in them, and had told him of them

in person. I am only the third person removed, yet I can relate

things that took place in Jersey County over two hundred years ago.

I remember this old Indian's (I will call him Chief hereafter)

description of their tribal wars and battles with the Okaws, Illinis

and other tribes now forgotten. Their last big battle was fought

against these tribes combined, and took place near where Delhi now

stands, between there and the Little Piasa, about a mile distant

from the village. Though only a boy of twelve, he took part in this

engagement (which must have been about 1772), fighting by the side

of his father. According to his statement, he did bravely, killing

several of the enemy with his arrows. The old chief took us over the

battleground and showed us where they had lain in ambush in the long

grass, and how the enemy had marched right up to them, without

suspecting their presence. They, thinking their march unknown,

intended to go down to the Little Piasa and cross it at what was

afterwards called Gardiner's ford, then take the "buffalo trail"

down by the "deer lick" and "buffalo wallow" to the Big Piasa and

attack them in the rear. But the Piasas, having gained information

of their coming, sprung a great surprise on them by ambushing them

on the route they knew they would take and completely defeating

them.

According to his account, great numbers were killed and many

wounded. I doubt the number killed, as I never knew any tribe to

face an enemy until their loss was very heavy. They will fight while

yelling, as only Indians can, but when a dozen or so are killed and

as many wounded, if one side does not run the other will. There are

only two ways that suit an Indian to fight, unless there are big

odds in his favor, that is from ambush, or on a run, either after

you, or from you. But, to return to my story - we boys often visited

the battlefield and where rain had washed little gullies, we would

often find a pocket full of stone arrow heads and judged that there

must have been a sure enough big fight there. He also told us of

another big battle, in which they were the victors, fought several

years before this (about 1767) near where the town of Jerseyville

now stands. The road from Jerseyville to Grafton passes over the

battlefield (or did), perhaps not over a mile distant from the

former place. I suspect boys have often found arrowheads there and

wondered how they come to be there in such quantities.

Growing weary of continual warfare over hunting grounds, his branch

of the Piasa tribe moved across and up the Mississippi (I have

forgotten at what date), joining a tribe of Algonquins, and made

their home in what is now Dakota. There he married, in after years,

his second wife, a half-blood, and when a girl was born he named her

Piasata (meaning crooked water) in remembrance of his tribe and

their former home on the Piasa. Piasata's success in shooting,

running and swimming is easily accounted for. Two villages stood

near each other, only a small stream separated them; the only

amusements the children had were swimming, running, or shooting with

bow and arrows and they grew up in daily practice of all three (when

weather permitted), the children on one village trying to outdo

those of the other; and Piasata became very expert in all three

amusements, as we boys afterwards found out. But it seems natural

for an Indian to be expert with bow and arrow. I have seen Indian

boys six or eight years old, who would knock a quarter out of the

end of a split stick, three times out of five, at ten or twelve

yards distance. It does not take one very long to get tired of

putting up quarters for them to shoot at, they getting the quarter

if they hit it first shot.

Chapter VI

This visit on which we met the old chief and his family was the

first time he had been to his boyhood's home since leaving it, which

was, I think, about 1780. They had come down the Mississippi and up

the Piasa in a large birch canoe, and had camped where their village

once stood, and he had erected his wigwam where his father's stood

when he was a boy. On a little hill nearby he showed us the graves

of his ancestors and told us that he wanted to see the old place

again before he went to the "Happy hunting grounds." Of course, he

told us this and many other things I have mentioned, after we

learned to speak his language. He told us also, as I have before

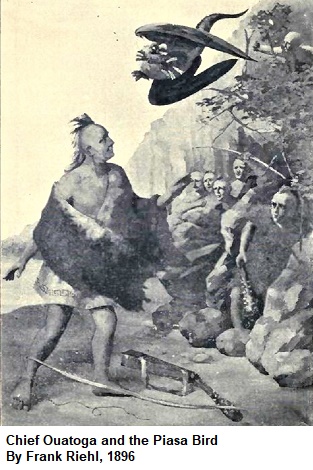

mentioned, about the "great Piasa bird;" how for a long time it

destroyed their children and even half-grown youths, and how, at

length, after a hard fight, they had succeeded in killing it. They

afterwards painted a picture of it on the bluff rocks on the

Mississippi at or near the mouth of the Piasa, where he said there

was a cave in which it lived. I never saw this picture, but have

often heard that it really existed, in fact have talked with persons

who said they had actually seen it. If painted there as he

described, and still visible, they must have used colors remarkable

for durability, as the work was done about 1690, over two hundred

years ago. This was in 1828, the old chief was then 67 years old,

and was born therefore about 1760, his father about 1735, his

grandfather about 1710 and his great-grandfather about 1680. It was

when his great-grandfather was a boy of ten or twelve that they

killed this great bird, and therefore about 1690. The way Indians

count by moons and seasons, they lose a year or over in every

twenty-five, and his great-grandfather was probably born about 1675,

and other dates given should be moved back accordingly.

I have heard traditions of this bird from other sources, both from

Indians and white people, but never believed that any such sized

bird as these traditions affirmed and he described, ever existed,

except in pre-historic ages. I am satisfied that a large, voracious

bird actually destroyed these youths or children, and was killed as

the old chief described. But from knowledge gained in after years

and from his description of its habits, its lofty flight a mere

speck in the sky and of its rapid descent on its prey and how it

could disable and even kill with the stroke of its wing or bill, I

believe that it was a huge Condor from the Andes mountains, which

had from some cause wandered that far from home and on account of

its solitary life, it became more daring and savage than usual and

attacked human beings instead of sheep or calves, there were none

there and in preference to eating carrion. Instances are not rare

where birds, large as well as small, have wandered thousands of

miles from home and never seemed to know how to return. But from

other descriptions he gave, I am satisfied that the "great Piasa

bird" was a lost or wandering Condor from some part of South

America.

Such is the legend of the bird and of its killing as told us by the

old chief on the banks of the Piasa in 1828.

Chapter VII

Strange as it may seem, the incidents which I have related refer to

things which are said to have happened on the Piasa 210 years ago

(1690), and yet the tale, tradition, or story, has passed through

but one person to me. The old Chief's great-grandfather lived to be

upwards of ninety, dying about 1772. When he was a boy of twelve, he

had often heard him relate the history of the bird, of its coming,

how it destroyed their children, and of its killing, and the part he

took in it, and as he (the old Chief) told these tales to me, they

have passed through but one person, though happening 210 years ago.

Time, and an Indian's imagination, no doubt added much to the size

of this bird, if not to its destructiveness. He pictured it as

twenty-five feet from tip to tip of wings, with a body as big as a

pony, and, when standing erect, seven or eight feet high. If, as I

believe, it was a large condor, its actual size was sufficient for

their imagination in after years to build up into the huge bird he

described. A large male condor will measure from fifteen to sixteen

feet from tip to tip of wings, having a body from three and a half

to four feet in length. The ferocity of the condor when hungry is

not equaled by any other bird. Though belonging to the vulture

class, it is also a bird of prey, and Woods, in his history of

birds, affirms that two of them have been known to kill full grown

sheep, lambs and even the savage puma, literally tearing them to

pieces with their terrible bills. In like manner, they have been

known to kill full grown cattle and to maim and cripple persons who

attempted to drive them away.

But, I must bring this story of early life in Jersey county to a

close, omitting much that I would like to tell, because the tale is

getting too long and I am tired of writing it. I pass over,

therefore, a description of the exhibitions the old Chief gave us of

his skill in the use of his war-bow and long arrows, as well as the

many strange Indian legends he told us and the history of his people

in the sha-shah (long ago). The month of November came on, and the

old Chief, his Indian name was Soan-ge-ta-ha (strong hearted), told

us that at the next new moon he would leave there and go back to his

people in the northwest. As this would occur in a few days, we boys

knew that we had but one more visit to make, and on that Sunday, I

shall never forget how each of us wore his best clothes and tried to

look his prettiest in order to charm the "running fawn," knowing it

was his last chance. But, somehow, before we arrived at their camp

we seemed to have a foreboding of evil. We talked it over, thinking

perhaps we would find that they were gone, or that Piasata was sick,

or anyhow that something strange had happened. When we got within a

half mile of the camp, we found Piasata's dog sitting in the road

awaiting our coming, something he had never done before, and he

looked cowed and downcast, as if he were in trouble. He trotted

along in front of us, straight up to the wigwam, and, to our

consternation, there lay our little Indian maiden as though she were

asleep, but she was dead.

I have often wondered if that dog could reason; he knew how we all

played together, as he was always with us and he knew that she was

dead. He had met us a long way from camp, seeming to know that it

was the day and hour that we made our regular visit, and he had led

us straight to the tent, looking first at her and then at us, as

though begging us to do something for her - to bring her to life

again. Tears were plentiful that morning, but the old Chief (stoic

all of them) shed not a single one. Yet his face and the twitching

of his muscles showed plainly his suffering. Her mother wept as

freely as ourselves, as she told us how she had been killed. She had

evidently climbed a tree to catch a bird she had wounded, when a

limb gave way and she fell to the ground, breaking her neck in the

fall. The dog came back without her and by his actions, got them to

follow him, when he led them to where she lay, but she was dead; her

neck was broken and she had evidently died without suffering, as

there was no trace of pain on features. Her mother had dressed her

in her best and brightest clothes, and she looked so natural that we

boys could hardly realize that our little We-ish-a-wa-sha had gone

from us forever. Her father, with tomahawk and other rude

implements, had dug a grave scarcely two feet deep, by those of his

ancestors, and there we boys, two at her head and one at her feet,

carried her on a dressed deer skin and gently lowered her body down

into it. Her mother then placed all of her trinkets and playthings

beside her, including all the gifts we had made to her, and then

folded the deer skin over her and she was hid from our sight

forever. With canoe paddles and hands, we boys filled up the grave

and shaped it as best we could, for our eyes were blinded with

tears. We thought it best to leave them alone in their sorrow, and

soon told them goodbye; her mother was weeping as freely as

ourselves, but the old Chief, in his own tongue without a quiver in

his voice, told each of us goodbye. Holding our hands in his, he

said that he would soon join Piasata in the happy hunting grounds

"beyond the sunset;" then exclaiming, "showain, showan, nemeshin (I

sorrow, I suffer, pity me), he turned and entered the tent and we

never saw him again.

On the following Sunday, we boys visited Piasata's grave and we saw

that it had been opened since we left. Wondering for what purpose

this had been done, we dug down a piece to make an examination, and

found her dog buried above her. Whether he had died from grief, or

whether the old Chief had killed him in order that he might go with

her to the "land of the Great Spirit," we, of course, could not

know, but from our knowledge of their belief, we judged that he had

not died a natural death.

Chapter VIII

Piasata, though only an ignorant Indian girl, managed and controlled

us boys equal to an experienced woman. An entire summer had passed,

and there had been no quarrels or contention between us, nor had we

been jealous of each other, because she made us believe that she

loved us all just the same. Only the week before her death, she drew

a circle in the dust, a heart inside of it, with three arrows just

touching the edge of the circle. The arrows represented us boys, and

in the Indian sign language, the figure meant that we were all equal

in her love or friendship.

Those unacquainted with the Indian sign language would be astonished

at the amount of information that can be conveyed through the medium

of a few little figures. We learned to write and read this language

from the old Chief and Piasata, and it afterwards proved to be of

great benefit to all of us, and especially to me, when on duty as a

scout. I have often read messages written on rocks, banks of clay,

or hard ground, intended for Indians only; thereby enabling me to

circumvent them. All Indian sign language is about the same; some

tribes use a few different figures to represent the same thing, but

in most cases, if you can read the sign figures of one tribe, you

can read those of another. I will mention one or two figures as used

by the Algonquins or Dakotas as a sample. A little tent or wigwam,

with a moccasin pointing towards it means, "Come to see me, you are

welcome." With the moccasin pointing from it, means "Keep away, I do

not want to see you." Strike a half circle two or three inches in

diameter, with the ends resting on a base line; the circle

represents the heavens, the base line the earth, the left-hand

corner represents sunrise, the center of circle - noon, and the

right-hand corner - sunset. If a wet day, a few little strokes or

lines extending downward from circle a half inch or more in length,

indicates it. If the forenoon is rainy, the lines are made between

center of circle (noon) and sunrise; or if the afternoon is wet

between the center and sunset. If you wanted to represent night, a

few little crossed lines are made for stars, while the same straight

lines are used to show whether raining or clear weather. If it is

desired to represent moonlight, the moon is shown whether full, old

or new, and the hour of night by its location on the circle. A full

moon is represented by a small circle, with two short lines crossing

in the center; an old one, by a half moon standing on end, and a new

one by same figure lying down, sharp ends pointing upwards. Indians

count time nearly invariably by the moon, from full to new moon and

from new to full moon. Thus, if a party writes a message at

midnight, ten days after full moon, the represent a full moon below

the base line of circle, then ten small dots or lines, with an old

moon in center of circle. If they should pass at nine o'clock a.m.,

they would show the sun half way between the sunrise and noon

points, with the age of the moon below base line, in the manner

already described. If the message is written by a war party, every

figure of a moccasin represents a warrior, and the course it points,

the direction they were traveling; while a figure of a pony with

dots after it indicates the number of ponies they had with them.

Thus, through this little figure, with a few short lines, small

crosses and circles, a party of Indians will leave a long and

accurate message to those who come after them.

Once, while in pursuit of a band of cut-throat Indians who had

committed some fiendish murders, our captain was about to give up

the chase, as I could not tell how far we were behind them. We knew

if we were then two days behind them, that they would gain the

mountains and make their escape, and we would have a long wearisome

ride for nothing. As we did not think that there were any Indians to

follow after them, we did not expect to find messages left for them

along the way. But just then, I discovered one written on a bank of

clay, and on deciphering it, found that there were eleven in the

party; that they passed there at about nine o'clock that day; that

the party had divided, five going to the right, the others to the

left, separating at an angle of about thirty degrees. We knew at

once that we had them. I knew the country as well as they did, and

knew that their separating and taking different routes was to

mislead us; as they were making for a certain pass and would meet

there again. By their angling route, they would lose many miles, and

we pushed straight ahead, taking a near cut and actually reached the

pass ahead of them. As it was dusk when they rode into it, they

could not see our trail, and we had them hemmed in before they

suspected our presence. We gave them a chance to surrender, but they

tried to break through our ranks and we just had to kill them. By

the message, we knew that another party was coming after them and we

got them also.

But to return to my story; forty years after the events I have

narrated took place, I was on business for a while in Dakota. There

were many Indians scattered about the place where I was located, and

I noticed one old squaw frequently stood and took a good long look

at me. One day I spoke to her kindly, asking her what she wanted.

She then came close to me and after another long look, she took my

hand and said: "Jim, Piasata," and I knew that she was her mother.

Indians sometimes forget a kindness, but never a feature or an

injury. She was old, wrinkled and ugly, but her heart was still warm

and tender in feeling, for the "running fawn" sleeping on the banks

of the distant Piasa. She told me that the Chief had been dead for

many years; that after Piasata's death, he "heap done nothing but

think," meaning that he had grieved his life away, thinking of the

loss of his child. We talked of the "olden times," and she was

greatly pleased to learn that I had a few years before made a

pilgrimage to Piasata's grave. I gave her a fine blanket and some

money, in remembrance of my little Indian sweetheart; and as I left

the next day, I never saw her again.

Chapter IX

Strange as it may seem, our meeting with the old Indian Chief and

his family marked out the destiny of us boys. We imagined that all

Indian girls were like Piasata and we talked "Algonquin" until our

parents wished that we had never seen an Indian. We covered nearly

everything we could write on, with figures of the sign language, in

fact, we used it when writing messages to each other. Upon one

occasion when my father was going over to Sam’s home, while I

pretended to dust off his coat, I shyly chalked a few figures on his

back for Sam’s eyes, and Sam actually succeeded in chalking an

answer on his coat tail. We talked of Indians and the great west

until we grew discontented, and at eighteen (1833), with our

parents' consent, we left home to seek our fortunes elsewhere.

Joe wandered all over the northwest as hunter, trader, scout or

trapper, as the occasion suited. He finally bought ten acres of

ground very cheap near the then small city of Chicago. The city grew

until finally it spread all around him and he sold out at a price

that made him rich. He died a few years ago at the age of 77. Sam

wandered over the west and southwest scouting, hunting and trading,

sometimes rich, sometimes poor, but finally settled down in

California in 1850. He died at the age of 79, leaving a fine estate

for his family.

As for myself, I had no thought when learning the Indian tongue and

to write and read the sign language of how useful it would be to me

in a few years afterwards. Thus, ends the history of three Jersey

county boys, We-ish-a-wa-sha, and the "great Piasa bird."

Post Script by the editor of The Daily Democrat:

In the letter which Mr. Wilson sent with his story was the following

account of his visit to Piasata's grave while on his visit to Jersey

County, which we did not publish in the introduction of the story

because of reference made to the grave of the "running fawn," and

other things not understood until after reading the chapters which

make up this interesting history of an Indian Chief and his family:

Chapter X

I got a horse and rode from Delhi over the old battle ground, and

down to Gardiner's Ford on the Little Piasa; then followed the old

"buffalo trail" (still traceable) to the "deer lick" and "buffalo

wallow." I afterwards visited the Big Piasa, but the roads had been

changed so much, that I secured a guide to pilot me there and back

again. We struck the stream at one of our favorite fishing places

and there found the ruins of a sawmill, old and about rotted away.

The guide said that it was called "Van Horne’s Mill" and it was

built perhaps by a relative of the Van Hornes I have mentioned. We

went down to where the old Chief had camped, but the open space

where the wigwam stood had grown up so thick with bushes and briars

that we could scarcely get through them. After considerable hunting,

I felt certain that I had located the grave of Piasata, the more so,

from some large pebble stones, which I remember the old Chief had

taken from the bed of the creek and placed around it. However, I

wanted to be certain about it and got the guide to go to a farm

house and get a spade. We then dug down a piece and soon turned up

the skull of a dog, and I knew her bones were resting beneath it. We

replaced the skull and fixed up the grave, and I gathered up a large

bunch of wild Sweet Williams and placed them on it, in memory of the

Indian girl we boys loved so well.

However, living among them cured our infatuation; we failed to find

any more Piasatas, and eventually married among our own people.

*******

EDITOR’S NOTES:

In the following information are details regarding the article

above, that will give further explanation to items mentioned in the

story:

The Piasa Creek referred to in this article, is the "Big Piasa

Creek,” which empties into the Mississippi near Lockhaven and the

Piasa Boat Harbor. Maps show the Piasa Creek runs throughout Jersey

(just south and east of Delhi) and Madison County, with many

branches. Some of these branches run through Madison County into

Alton, Illinois. "Little Piasa" Creek runs through Macoupin County

into Madison County.

According to James Wilson's statement above, he was born about 1815.

According to Civil War records, there was a James R. Wilson enlisted

in the Confederate Army, 45th Mississippi Infantry, Company E,

"McNair Rifles," as a Second Lieutenant. He enlisted at Natchez, and

resigned in March/April 1862. At the time of his enlistment in 1861,

he was age 32 (according to their records), and would have been born

approximately 1829. The McNair Rifles Unit was raised in Pike

County, Mississippi. The city of McComb, in which the James Wilson

who wrote this story lives, is in Pike County, Mississippi. However,

it is unproven if these two James Wilson’s are one of the same.

The Indian Maiden in this article, Piasata, was supposedly named

after Piasa Creek, which means "Crooked Water." Maps show the Piasa

Creek is indeed very crooked and winds throughout Jersey and Madison

Counties.